Giving a system T that is ``derived'' from the system S by

substituting the variables by polynomial functions of another set of

r variables is a natural operation on systems of equations. The

analogous notion is that of a morphism of functors (also called a natural transformation) F![]() G. This is a way of giving a map

F(A)

G. This is a way of giving a map

F(A)![]() G(A) so that for any ring homomorphism A

G(A) so that for any ring homomorphism A![]() B we get a

commutative diagram (any element in the top left corner has the

same image in the bottom right corner independent of the route

followed).

B we get a

commutative diagram (any element in the top left corner has the

same image in the bottom right corner independent of the route

followed).

| F(A) | G(A) | |

| F(B) | G(B) |

For those who have studied affine schemes earlier in a slightly different way we offer the following result which is proved in the second appendix.

A slightly different example (but one which is fundamental) is the

functor that associates with a ring A the collection of all

n + 1-tuples

(a0, a1,..., an) which generate the ring A upto

multiplication by units. Equivalently, one can think of all surjective

A-module homomorphisms

An + 1![]() A modulo the equivalence induced

by multiplication by units. This functor is denoted

A modulo the equivalence induced

by multiplication by units. This functor is denoted

![]() n and is

conceptualised as the projective n-dimensional space. We use the

symbol

(a0 : a1 : ... : an) to denote the equivalence class under

unit multiples of the n + 1-tuple

(a0, d1,..., an) which gives

rise to an element in

n and is

conceptualised as the projective n-dimensional space. We use the

symbol

(a0 : a1 : ... : an) to denote the equivalence class under

unit multiples of the n + 1-tuple

(a0, d1,..., an) which gives

rise to an element in

![]() n(A).

n(A).

Now, if

a = (a0 : a1 : ... : ap) and

b = (b0 : b1 : ... : bq) are

elements in

![]() p(A) and

p(A) and

![]() q(A) respectively, then we can form

the

(p + 1) . (q + 1)-tuple consisting of

cij = aj . bj; this

tuple generates the ring A as well. Clearly, when a and b are

replaced by unit multiples ua and vb for some units u and v in

A, the tuple

c = (cij)i = 0, j = 0p, q is replaced by its unit

multiple (uv)c. Thus, we have a natural transformation

q(A) respectively, then we can form

the

(p + 1) . (q + 1)-tuple consisting of

cij = aj . bj; this

tuple generates the ring A as well. Clearly, when a and b are

replaced by unit multiples ua and vb for some units u and v in

A, the tuple

c = (cij)i = 0, j = 0p, q is replaced by its unit

multiple (uv)c. Thus, we have a natural transformation

![]() p×

p×![]() q

q![]()

![]() pq + p + q. Moreover, one easily checks

that the resulting map on sets

pq + p + q. Moreover, one easily checks

that the resulting map on sets

For each positive integer d we can associate to

a = (a0 : a1 : ... : ap) the

![]() tuple of all monomials

of degree exactly d with the entries from a. For example, if d = 2

then we take the

tuple of all monomials

of degree exactly d with the entries from a. For example, if d = 2

then we take the

![]() -tuple consisting of

bij = aiaj.

As above this gives a natural transformation of functors

-tuple consisting of

bij = aiaj.

As above this gives a natural transformation of functors

![]() p

p![]()

![]()

![]() - 1. For each finite ring A the

resulting map on sets

- 1. For each finite ring A the

resulting map on sets

The two examples above are special cases of projective subschemes defined as follows. Let F(X0,..., Xp) be any homogeneous polynomial in the variables X0,...,Xp (in other words all the monomials in F have the same degree). While the value of F at a p + 1-tuple (a0,..., ap) can change if we multiply the latter by a unit, this multiplication does nothing if the value is 0. Thus, the set

There is also a natural way of thinking of affine schemes in

terms of subfunctors of

![]() n for a suitable n. As we saw above

any affine scheme is a subscheme of

n for a suitable n. As we saw above

any affine scheme is a subscheme of

![]() q, so it is enough to

exhibit

q, so it is enough to

exhibit

![]() q as a subfunctor of

q as a subfunctor of

![]() n for a suitable n. Now it

is clear that if

(a1,..., aq) is any q-tuple, then the

collection

(1, a1,..., aq) generates the ring A so that this

defines an element

(1 : a1 : ... : aq) of

n for a suitable n. Now it

is clear that if

(a1,..., aq) is any q-tuple, then the

collection

(1, a1,..., aq) generates the ring A so that this

defines an element

(1 : a1 : ... : aq) of

![]() q(A). Conversely, if

(a0 : a1 : ... : aq) is an element of

q(A). Conversely, if

(a0 : a1 : ... : aq) is an element of

![]() q(A), such that a0

is a unit then this is the same as

(1 : a1/a0 : ... : aq/a0), which

in turn corresponds to the point

(a1/a0,..., aq/a0) in

q(A), such that a0

is a unit then this is the same as

(1 : a1/a0 : ... : aq/a0), which

in turn corresponds to the point

(a1/a0,..., aq/a0) in

![]() q.

q.

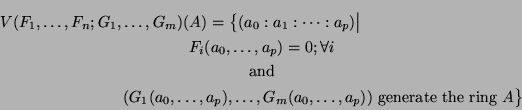

A generalisation of the above is the notion of a quasi-projective scheme. In addition to the homogeneous polynomials Fi considered above let G1(X0,..., Xp), ..., Gm(X0,..., Xp) be homogeneous polynomials of the same degree. We define a quasi-projective scheme

One can go further and define the notion of an abstract algebraic scheme but for our purposes the notion defined above of a quasi-projective scheme (of finite type over integers or of ``arithmetic'' type) will suffice.

Let F1,...,Fn be a collection of equations which define a projective scheme and d be no smaller than the maximum of their degrees. It is clear that the same projective scheme is defined by the larger collection of the form Fj . M where j varies between 1 and n and M varies over all monomials of degree d - deg(Fj). Thus we can always assume that a projective scheme is defined by homogeneous equations of the same degree.

The complement of the subscheme of

V(F1,..., Fn) is not the functor that assigns to each A the set-theoretic

complement

![]() p(A)

p(A) ![]() V(F1,..., Fn)(A), but in fact,

when Fi's have the same degree it is the quasi-projective scheme

V(0;F1,..., Fn)(A). The reason for this choice becomes clear as

we study schemes more. For the moment it is enough to note that if

A is the ring

V(F1,..., Fn)(A), but in fact,

when Fi's have the same degree it is the quasi-projective scheme

V(0;F1,..., Fn)(A). The reason for this choice becomes clear as

we study schemes more. For the moment it is enough to note that if

A is the ring

![]() p[

p[![]() ] =

] = ![]() p[X]/(X2), then the element

(1 :

p[X]/(X2), then the element

(1 : ![]() : ... :

: ... : ![]() ) is in the set-theoretic complement of

(1 : 0 : ... : 0) in

) is in the set-theoretic complement of

(1 : 0 : ... : 0) in

![]() p(A) but is not in the scheme-theoretic

complement that we have defined above.

p(A) but is not in the scheme-theoretic

complement that we have defined above.

Finally, let

X ![]()

![]() p be a quasi-projective scheme, and let

F1,..., Fn be a bunch of homogeneous polynomials of the same

degree. The intersection

X

p be a quasi-projective scheme, and let

F1,..., Fn be a bunch of homogeneous polynomials of the same

degree. The intersection

X ![]() V(F1,..., Fn;1) is clearly a

subscheme of X and such subschemes are called closed

subschemes of X. The intersection

X

V(F1,..., Fn;1) is clearly a

subscheme of X and such subschemes are called closed

subschemes of X. The intersection

X ![]() V(0;F1,..., Fn) is also

a subscheme of X and such subschemes are called open subschemes of

X. More generally, the intersection of

V(D1,..., Dm;E1,..., En) and

V(F1,..., Fk;G1,..., Gl)

is the scheme

V(0;F1,..., Fn) is also

a subscheme of X and such subschemes are called open subschemes of

X. More generally, the intersection of

V(D1,..., Dm;E1,..., En) and

V(F1,..., Fk;G1,..., Gl)

is the scheme

One very useful example of a closed subscheme is the subscheme

![]() p

p ![]()

![]() p×

p×![]() p, which is the diagonal; this is a

closed subscheme of the scheme

p, which is the diagonal; this is a

closed subscheme of the scheme

![]() p×

p×![]() p defined by the

conditions

XiYj = XjYi for

0

p defined by the

conditions

XiYj = XjYi for

0 ![]() i, j

i, j ![]() p. For any p < q we can

exhibit

p. For any p < q we can

exhibit

![]() p as the closed subscheme of

p as the closed subscheme of

![]() q given by Xi = 0

for p < i

q given by Xi = 0

for p < i ![]() q.

q.

Like the case of set-theoretic complement, the set-theoretic union of

closed subschemes is in general not a closed subschemes. For example

the smallest closed subscheme of

![]() 2 that contains L = V(X1) and

M = V(X2) is easily seen to be V(X1X2); but it is possible for

the product of two elements of a finite ring to be 0 without either of

them being zero. Thus we can define the scheme-theoretic

union of a collection of closed subschemes to be the smallest closed

subscheme that contains the set-theoretic union (the set-theoretic

union defines a subfunctor); such a scheme exists by Hilbert's basis

theorem. From now on when we use the term union of schemes we shall

always mean the scheme theoretic union.

2 that contains L = V(X1) and

M = V(X2) is easily seen to be V(X1X2); but it is possible for

the product of two elements of a finite ring to be 0 without either of

them being zero. Thus we can define the scheme-theoretic

union of a collection of closed subschemes to be the smallest closed

subscheme that contains the set-theoretic union (the set-theoretic

union defines a subfunctor); such a scheme exists by Hilbert's basis

theorem. From now on when we use the term union of schemes we shall

always mean the scheme theoretic union.

A closed subscheme

Y ![]() X is said to be a proper closed

subscheme if for some finite ring A, the subset

Y(A)

X is said to be a proper closed

subscheme if for some finite ring A, the subset

Y(A) ![]() X(A)

is a proper subset. A scheme is said to be reducible if it can

be written as the union of two distinct (but not necessarily

disjoint!) proper closed subschemes. For example V(X1X2) in

X(A)

is a proper subset. A scheme is said to be reducible if it can

be written as the union of two distinct (but not necessarily

disjoint!) proper closed subschemes. For example V(X1X2) in

![]() 2) is the union of the two lines V(X1) and V(X2). Now

even a proper closed subscheme

Y

2) is the union of the two lines V(X1) and V(X2). Now

even a proper closed subscheme

Y ![]() X can be ``essentially'' all

of X; for example consider the closed subscheme

Y = V(X22) of the

scheme

X = V(X23). For any finite field F, we have

Y(F) = X(F). A scheme X is said to be reduced if it has no

proper closed subscheme Y such that Y(F) = X(F) for all finite

fields F. Note that the scheme V(X1X2) is reduced but not

irreducible, while V(X12) is irreducible but not reduced.

Hilbert's Basis theorem can also be used to show that any scheme X

has a closed subscheme Y so that Y is reduced and Y(F) = X(F) for

finite fields F. As a consequence of the Lasker-Noether Primary

Decomposition theorem any scheme can be written as the union of a

finite collection of irreducible closed subschemes; moreover, the

underlying reduced schemes of these closed subschemes are uniquely

determined. For example, consider the scheme

L = V(X12, X1X2) in

X can be ``essentially'' all

of X; for example consider the closed subscheme

Y = V(X22) of the

scheme

X = V(X23). For any finite field F, we have

Y(F) = X(F). A scheme X is said to be reduced if it has no

proper closed subscheme Y such that Y(F) = X(F) for all finite

fields F. Note that the scheme V(X1X2) is reduced but not

irreducible, while V(X12) is irreducible but not reduced.

Hilbert's Basis theorem can also be used to show that any scheme X

has a closed subscheme Y so that Y is reduced and Y(F) = X(F) for

finite fields F. As a consequence of the Lasker-Noether Primary

Decomposition theorem any scheme can be written as the union of a

finite collection of irreducible closed subschemes; moreover, the

underlying reduced schemes of these closed subschemes are uniquely

determined. For example, consider the scheme

L = V(X12, X1X2) in

![]() 2. One can show that that L is the union of the closed

subschemes M = V(X1) and

N = V(X12, X1X2, X22). But L can also

be written as the union of M and

K = V(X12, X0X2, X1X2, X22);

moreover N and K are distinct schemes.

2. One can show that that L is the union of the closed

subschemes M = V(X1) and

N = V(X12, X1X2, X22). But L can also

be written as the union of M and

K = V(X12, X0X2, X1X2, X22);

moreover N and K are distinct schemes.